The planning for our Boundary Waters trip began back in February. Unlike past challenges, this one involved much more than just physical training. It required a lot of logistics. We had originally planned for six people to join, which was exciting but also touched on one of my biggest weaknesses - organization. My lack of navigational skills would also be exposed later in the trip.

To get started, I reconnected with an old high school classmate, Mat Krueggberg. He was the main reason I passed AP Statistics, though I had not spoken with him in nearly ten years. Since 2020, Mat had been heading up to the Boundary Waters three to four times a year, and he seemed like the perfect person to ask for advice. I set up a call to learn how to register for a permit, plan a route, pack, and pick up a few helpful tricks such as wearing wool socks. I made the call right after finishing my Oral English class in China, forgetting to disconnect my screen from the Smartboard. As a result, my students were unexpectedly treated to a Minnesotan-style conversation between two old friends.

Afterward, Brian and I sat down to reserve permits and plan a route. The Boundary Waters is massive, covering 1.1 million acres with over 1,100 interconnected lakes. It stretches past the boundary lines separating Minnesota and Canada, and is located directly west of Lake Superior. When we pulled up the map with its 84 entry points, the scale was overwhelming. After an hour of zooming in and out, we finally picked a route. But when we tried to book it, we discovered that every permit for July and August was already taken. It felt like trying to get a table at an exclusive restaurant, we were trying to making reservations three months early, which meant we were already three months too late. Each entry point only allows a set number of canoes each day to preserve the wilderness and ensure enough campsites. That night, I left Brian’s house thinking the Hope in Motion Boundary Waters trip would have to wait until 2026.

Instead, we turned to outfitters. These are companies near the Boundary Waters that can help with permits, gear, and routes. Most importantly, they monitor cancellations and can act quickly when a spot opens up. We sent out ten emails, and eventually one outfitter came through with a permit for July 21 at the very entry point we had wanted. The only catch was that my work in China ended on July 18. I told myself I could handle being jet lagged and water legged if it meant getting to go. For the next month and a half, our main focus was collecting gear and supplies.

Then, in late June, our six-member team began to feel like characters in Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None. Brian broke his ankle. We optimistically tried to move the trip to mid-August, naively thinking he would be healed in time, but his doctor quickly ended that idea. He would not even be able to put weight on his foot until mid-August, let alone carry a sixty-pound pack over up and down rocky terrain. With Brian out, his nephew had to drop as well, leaving us with four, an ominous number in Chinese culture. And the unfortunate events kept coming.

In mid-July, another teammate had to withdraw because of a cancer recurrence in her family. While our group had some outdoor adventure experience, it paled in comparison to hers. I had been counting on her to help share the workload and add an extra layer of safety. Losing her made me seriously consider calling off the whole trip.

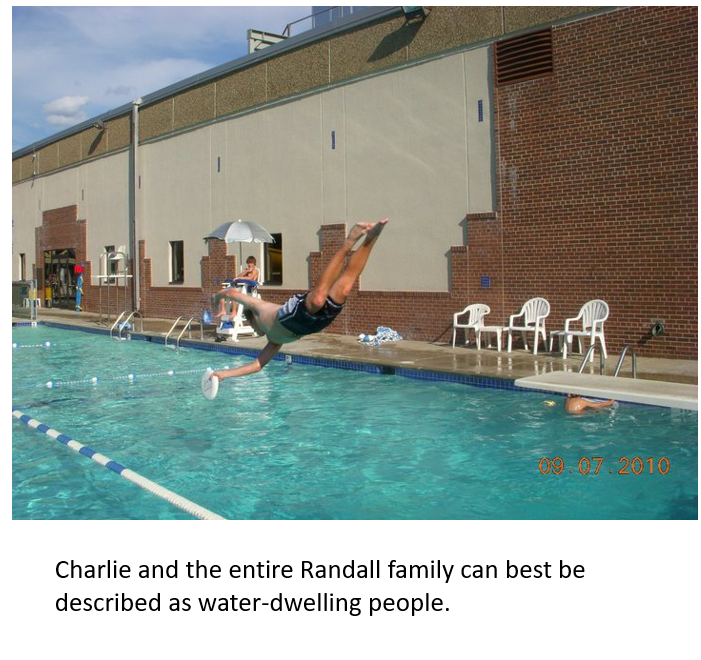

But Charlie Randall, the rockstar, thought we could still make it work. He had been to the Boundary Waters several times before and knew what to expect. Together, we built a checklist of essentials and mapped out a daily itinerary. The supply list felt endless. We decided to rent cookware and order meals from the outfitter, and Charlie reached out to friends and friends of friends to borrow nearly everything else we needed.

The planning had been far from smooth sailing, but we pressed on with plans to go on anyway, just the three of us.

Create Your Own Website With Webador