Day 1 Part 1 – The Big Kahuna (August 11)

I woke up that morning feeling like a year had passed, which was technically true; at midnight, I had turned 37. After repacking my bag for what felt like the zillionth time, we headed down for a Paul Bunyan–sized breakfast. Lionel, however, seemed to be starting the day with a streak of clumsiness: first spilling his hot chocolate, then stumbling to get down from his high chair. If Charlie had any concerns about taking a near–50 mile canoe trip with this boy, he never let it show. I, on the other hand, was beginning to feel a bit apprehensive about the trip.

After breakfast, we checked in at the main office to confirm our reservation. The staff had us watch a rules-and-regulations video. Lionel, ever the law-abiding citizen, seemed to memorize every single bullet point. (Foreshadow: “No, Dad, we can’t swim right now—you just sprayed bug spray on me! Don’t you remember the video?”). Somehow, he managed to absorb every detail except the part about keeping your voice down at campsites.

A knowledgeable guide then walked us through our route, warning us about windier stretches and pointing out possible bail-out options “if things got hairy.” He explained how to tie and hang our food pack properly so that bears wouldn’t come sniffing around. I always beg my students to ask questions when I teach, and I usually plead with them to ask at least one to clear up any confusion and allow me to have some insight into what they understand. But when this guy wrapped up his talk and asked us if we had any questions, I swallowed the ten or so that immediately came to mind. “Nope, I think we got it,” I said out loud, terrified that if I admitted what I didn’t know, he’d reroute us somewhere easier or insist we hire a guide.

Outside, the Voyager’s staff helped us load bags and secure the canoe on top of a shuttle van. Our entry point was about seven miles south. As we pulled away, the driver radioed in our drop-off at Checkpoint 54. When she heard our ambitious plan, her eyebrows lifted, and she gave an “ohhh” that read more like, good luck with that. Once we turned off the main road, we flew down gravel hills. Lionel threw his arms up like he was on a rollercoaster and shouted “Whoooopie!”

Fifteen minutes later, we were at the entry point. The Boundary Waters has a beautifully frustrating trait: no unnatural signs. Nothing to confirm where you are. Charlie checked the map twice and checked with our driver before we shoved. Loading gear into the canoe, I finally felt the true weight of everything we were bringing, our food pack our food pack alone could have anchored a small ship.

Our canoe setup was Lionel in the bow, Charlie in the middle (which is really closer to the stern), and me steering in the back. In a three-person canoe, the heaviest person sits in the middle for balance. I hadn’t paddled with another adult since… I was a kid. Charlie, though, attacked the water like he was a competitor in a dragon boat race. Matching stroke cadence is everything in a canoe, you move faster and save energy. But to keep up, I had to go double-time my own strokes, like a bad Tae Bo routine. We started out at an Olympic pace, with one small problem, I am not, and never have been, in Olympic shape. Still, I didn’t want to be the first to quit, so I sweated and gritted my teeth to keep us moving.

Sitting in the stern meant steering duty fell squarely on my shoulders. Before the trip, I’d spent time practicing the “J-stroke,” a supposed essential method for managing the direction of your canoe. The motion starts like a regular forward stroke, but just as the blade reaches your hip, you twist your wrist and push the paddle outward in a small hook, tracing the letter J in the water. Done right, it keeps the canoe gliding straight without losing speed. Skip it, and you’re left with the “goon stroke,” which yanks the bow in the opposite direction of your paddle meaning you will have to keep switching the sides you paddle on as you zigzag across the lake.

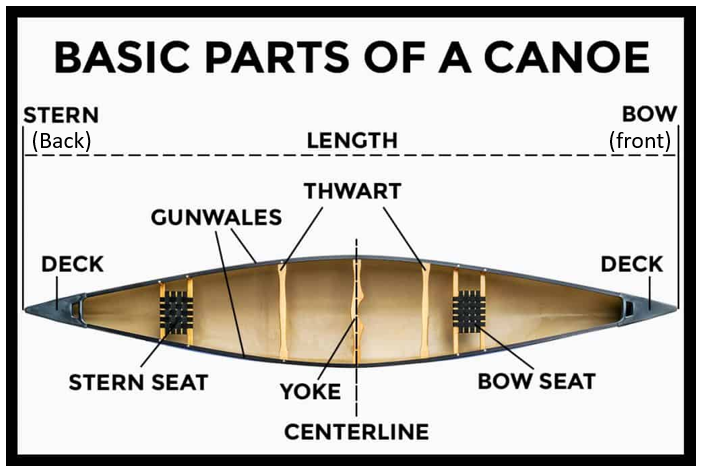

Since Charlie was paddling from the middle and had to reach farther out over the gunwale, his powerful strokes constantly pulled us off course. Instead of relying on my neat little J-stroke to keep us aligned, I had to throw in a wider corrective stroke every fourth pull just to counteract his horsepower. Steering, I managed “mostly okay” that first day. My bigger failure came with my second responsibility: navigation. On the map, every island’s contour looked identical to its neighbor. More often than not, I was off by a mile or two in guessing where we were. At one point, I outrageously proclaimed that we should be nearing our first portage. If that had been the case, it would have meant we paddled the entire stretch of “Three-Mile Island” in about 15 minutes. (For reference: a canoe averages about two miles per hour.)

Two hours in, I felt the creeping numbness in my left leg that had bothered me for months. My sister, a physical therapist, had already diagnosed me the previous week as the least flexible thirty-something she had ever seen. I was probably dealing with sciatic nerve irritation, and the way I was sitting in the canoe was exacerbating it. Luckily, we had folding chairs for the canoe. Once I leaned back and “rowed with it,” the numbness subsided, and my strokes suddenly felt stronger with half the effort.

By midday, we hit our first portage—a third of a mile of rocky trail, and thankfully the longest one of the entire trip. Charlie wanted to conquer it in a single haul, stacking backpacks front and back while balancing the canoe on his shoulders. Foolishly, I copied him, piling seventy-five pounds on my back and loading up both hands before realizing, about six steps in, that this was Herculean madness. I wasn’t wise enough, however, to ditch the second backpack, and so I trudged through a hellacious trek, trying to patiently guide Lionel across the uneven path while feeling like I carried the weight of the world on my shoulders. Meanwhile, Charlie powered through the portage twice without a grimace, a true manimal. I was deeply grateful to slip the canoe back into the water, if only for a while longer.

POV from Charlie carrying the canoe. Charlie was able to carry the canoe by himself each portage by placing the yoke on his shoulders.

Create Your Own Website With Webador